What is an Ectopic Pregnancy?

It occurs when an ovum (egg) that has been fertilised implants (“gets stuck”) outside the cavity (“space”) of the uterus (womb). The most common place for an ectopic pregnancy is the Fallopian tube but there are many other sites where an ectopic pregnancy can be located. It is, sadly, not possible to move an ectopic pregnancy into the uterus.

Each month, during the menstrual cycle, ovulation occurs where one of the ovaries produces an egg that is drawn into the end of the Fallopian tube by finger-like structures called fimbriae. The egg then makes its way along the Fallopian tube towards the uterus. During the course of this journey, if intercourse (sex) has occurred, it may encounter sperm, in which case it may become fertilised.

If it is fertilised, the egg implants itself into the lining of the uterus called the ‘endometrium’ and ultimately grows into a baby. If it is not fertilised, then both the egg and uterus lining are discharged in the menstrual flow (period), a fresh lining is prepared, and a new egg begins to mature within the ovary.

What happens if you have an ectopic pregnancy?

With an ectopic pregnancy, the fertilised egg becomes caught or delayed while progressing along the Fallopian tube. In this case, the pregnancy continues to grow inside the Fallopian tube where it can cause the Fallopian tube to burst or severely damage it. This can sometimes cause internal bleeding causing pain and requiring immediate medical attention.

How many are affected by the condition?

Each year in the UK, nearly 12,000 women have ectopic pregnancies diagnosed (Source: 2024 MBRRACE-UK Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2020–22). From anecdotal evidence, it is believed the number of cases of ectopic pregnancy may number more than 30,000 per year in the UK alone.

The 2024 MBRRACE-UK Report 2020-22 shows that ectopic pregnancy remains the most frequent cause of maternal death in early pregnancy. The MBRRACE team identified concerns over the number of deaths due to ectopic pregnancy which led to the review of deaths due to early pregnancy causes occurring in 2021-22 being “expedited” – meaning this review happened more quickly.

During such two-year period in the UK and Ireland, 12 women died from an early pregnancy-related cause. These were all due to ectopic pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancy deaths have risen again – from 5 reported in 2019, to 8 in the 2022 report, to now 12. This is an alarming trend and ectopic pregnancy deaths in this report is almost twice the rate in 2018-20.

The report states that all 12 women who died from an ectopic pregnancy could have had better care. Improvements to care may have made a difference to the outcome for nine women (75%).

You can read our statement here.

MBRRACE-UK Maternal Report 2016

MBRRACE-UK Maternal Report 2019

MBRRACE-UK Maternal Report 2022

MBRRACE-UK Maternal Report 2024

Sadly, there are on average six deaths per year in the UK and Ireland due to ectopic pregnancy. In the 21st century, no woman should die of an ectopic pregnancy. Depending on individual medical circumstances, several treatments are available. The pregnancy can never be saved.

The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust believes that the deaths and trauma associated with ectopic pregnancy should be prevented. We seek to relieve the distress associated with the experience and provide ongoing support through their treatment and beyond.

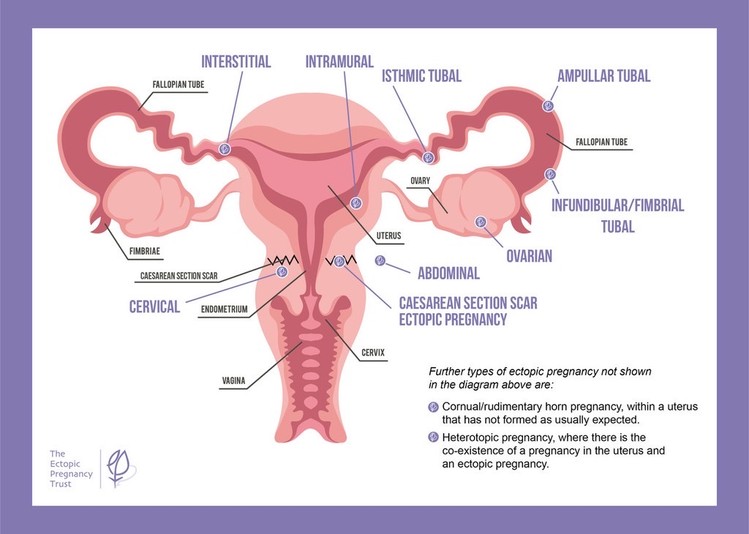

What are the different types of ectopic pregnancy?

- 95% are in the Fallopian tube – either ampullary (in the middle part of the Fallopian tube), isthmic (in the upper part of the Fallopian tube close to the uterus) or fimbrial (at the end of the tube)

- 3% are interstitial (inside the part of the Fallopian tube that crosses into the uterus)

- < 1% are within a Caesarean section scar on the uterus

- < 1% are cervical (on the cervix)

- < 1% are cornual (within an abnormally shaped uterus)

- < 1% are ovarian (in or on the ovary)

- < 1% are intramural (in the muscle of the uterus)

- < 1% are abdominal (in the abdomen)

- < 1% are heterotopic pregnancies

This image shows where ectopic pregnancies are most likely to occur:

Types of Ectopic Pregnancy in more detail:

Tubal ectopic pregnancy - ampullary, isthmic and fimbrial

The Fallopian tubes are small, hollow muscular tubes, each about ten centimetres long. The outer half lies next to, but not attached to, its ovary. The Fallopian tubes have a delicate mucous membrane lining inside the tube, thrown up into folds, which almost fill each tube. The diameter and the number of folds increase as the Fallopian tube nears the ovary and forms the fimbriae – tiny finger-like projections that move and create a suction effect to draw the egg to the Fallopian tube.

In the lining of the Fallopian tubes, half the cells are mucus-secreting and half have cilia – tiny hair like projections which waft gently to propel these secretions towards the uterus. The Fallopian tube has a natural peristaltic action (contraction and relaxation to create a pumping effect) which assists the movement of mucus.

An egg, released at ovulation, is picked up by the Fallopian tube fimbriae, and the Fallopian tube is responsible for the transport of the fertilised egg to the cavity of the uterus which takes about four days. If a pregnancy is as expected, a bundle of sixty-four cells reaches the uterus to implant six to seven days after ovulation, by which time the natural female hormones have prepared the uterine lining cells (endometrium). The embryo burrows into the endometrium and starts to form a placenta.

Where pregnancies do not reach the uterus, it is not difficult to imagine how the delicately folded Fallopian tube linings with specialised cells can become damaged by inflammation or infection, and/or the transportation of a developing embryo to the uterus may be slow for no obvious reason. In the meantime, the embryo is still trying to develop and has a natural invasive nature, so it can implant in the Fallopian tube or fimbriae to form a placenta, resulting in a potentially dangerous ectopic pregnancy.

Interstitial pregnancy

An interstitial pregnancy is a rare type of ectopic pregnancy that occurs when the fertilised egg implants in the part of the Fallopian tube as it crosses the wall of the uterus.

Pregnancies of this kind are difficult to diagnose as they may appear to be in the uterus on a scan or may be difficult to see on scan very early on. They are particularly dangerous if they are growing as they can progress further and tend to rupture later, having the potential to damage both the wall of the uterus and the Fallopian tube.

If diagnosed early enough, doctors may recommend medical treatment with methotrexate if suitable, as surgery for an interstitial pregnancy can involve surgery to the actual uterine wall and this could result in the uterus being weakened. Some interstitial ectopic pregnancies may not be growing and may even resolve without any active treatment.

It is possible to have successful uterine pregnancies after an interstitial pregnancy. Your doctor will assess you carefully and consider the need for an elective caesarean section to deliver any subsequent pregnancy and the preferred method of delivery will depend on the extent of the surgery necessary on the uterine wall to resolve the ectopic pregnancy.

Some doctors call interstitial pregnancies ‘cornual’ which is confusing, so the term ‘interstitial’ is preferred.

Caesarean scar pregnancy

Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancies are when the fertilised egg implants into the gap in the muscle of the uterus caused by a previous Caesarean section. The pregnancy may then grow out of the uterus or onto the cervix and cause torrential internal or vaginal bleeding.

In some pregnancies the placenta develops so that only part of it is within the scar and these pregnancies may proceed to delivery of a live baby, but with risk of significant bleeding from the mother and hysterectomy at the time of delivery.

The treatment of caesarean scar pregnancies is potentially difficult so management has to be individualised on a ‘case by case’ basis.

Most Caesarean scar pregnancies can be treated by removing the pregnancy using suction. If the pregnancy cannot be reached using suction, then keyhole surgery, or methotrexate injection/s can be used.

Research indicates that this kind of ectopic pregnancy appears to be increasing, possibly due to the impact of elective caesarean section delivery which was much less common 10 years ago than today. However, despite appearing to increase in incidence, they are still relatively uncommon and so some hospitals see very few of them. Accordingly, there are moves to focus care in these cases to regional units with experience of these cases both to optimise care and to collate information to make sure there is a better evidence base to inform treatment decisions in the future.

Cervical pregnancy

Cervical pregnancies are one of the rarest forms of ectopic pregnancy and are thought to be of special concern because of the risk of life-threatening vaginal haemorrhage. The cervix is highly vascular (lots of blood vessels) and, when the pregnancy separates from the cervix blood transfusions are usually essential.

An emergency hysterectomy has historically been the only option as the diagnosis was not often made before rupture; however, planned conservative management of a cervical ectopic pregnancy using suction evacuation with a cervical stitch or methotrexate are now potential treatments to preserve fertility if the diagnosis is made before it becomes an emergency. Scarring of the passage through the cervix due to gynaecological procedures has been identified as one of the leading risk factors for a cervical ectopic pregnancy.

Cornual or Rudimentary horn pregnancy

This is another rare type of ectopic that only occurs in a uterus that has not formed as expected.

A uterus that develops as expected is when two halves join together. However, sometimes these two halves do not meet and this leaves one banana-shaped (unicornuate) side which is in contact with the cervix and vagina and another nubbin of uterus on the opposite side (that is not usually in contact with the cervix and vagina, called a rudimentary horn). Both sides have their own Fallopian tube. Sperm can reach deep inside via the one-sided uterus that is in contact with the vagina, but the opposite Fallopian tube may pick up the fertilised egg and transport it into the rudimentary horn.

Because the rudimentary horn often has a thick muscular wall, these pregnancies may advance into the second or even third trimester before they cause catastrophic rupture. The thick wall also makes them more difficult to diagnose, as the rudimentary horn may be assumed to be a normal uterus during an ultrasound scan.

Treatment is to terminate the pregnancy by surgically removing the rudimentary horn and its Fallopian tube. If the pregnancy is advanced, this is sometimes difficult to do without also removing the ovary on the same side.

A pregnancy in the uterine portion of the Fallopian tube of a uterus that forms as expected is called an interstitial pregnancy. This should not be confused with a cornual pregnancy.

Ovarian pregnancy

Ovarian ectopic pregnancies are the rarest type making up less than 1% of all ectopic gestations.

These are difficult to diagnose as they look very similar to a tubal ectopic pregnancy that is stuck to the ovary or a ‘corpus luteum’ which is the place that the egg was released from. This can mean that ovarian pregnancies are often not diagnosed until surgery.

The ovary is a highly vascular structure. An ectopic pregnancy located on or in the ovary will usually require surgery involving either the partial or complete removal of the ovary due to bleeding. If the ovary is partially removed, it may recover and continue to produce eggs as before.

However, even if it no longer produces eggs or is removed completely, the other ovary is perfectly capable of producing an egg every cycle, enabling the ability to conceive naturally in the future.

Intramural pregnancy

This is a term that means ‘in the wall’ and refers to a pregnancy that implants outside the cavity of the uterus, but within its muscular wall.

These pregnancies are thought to occur when the uterus has been scarred by previous surgery or a condition called adenomyosis. Again, they can be difficult to diagnose as it can be hard to see the cavity as separate to the pregnancy. The pregnancies are also inaccessible, which makes them difficult to treat by removing the pregnancy. Methotrexate may be advised.

Abdominal pregnancy

Abdominal pregnancies, in most instances, are thought to have begun in the Fallopian tube and then separated from the wall of the fallopian tube, floating into the abdominal cavity to then reattach to one of the structures in the abdomen.

The pregnancy can progress and may go undetected until many weeks into the pregnancy. There are some accounts of abdominal pregnancies surviving to be delivered with an abdominal operation but these are incredibly rare.

Heterotopic pregnancy

Heterotopic pregnancy is the term where there is the co-existence of an intrauterine pregnancy with an ectopic pregnancy. Although it is rare, it is possible to have a twin pregnancy with one embryo to implant in the uterus and another elsewhere.

It is possible for the co-existing intrauterine twin to survive in approximately 30% of diagnosed cases of heterotopic pregnancy, even if treated surgically for the condition. Some studies suggest that the live birth rate of a surviving pregnancy may even be higher if it is in the uterus and developing as expected at the time of diagnosis.

Other pages you might find helpful

Are you experiencing symptoms that you think may be an ectopic pregnancy? Click here to find out more.

This section aims to help you make sense of some of the thoughts, feelings, and reactions you may be experiencing.